Buying a home is the embodiment of the American dream. However, that wasn’t always the case: In fact, before the 1930s, only four in 10 American families owned their own home. That’s because very few people had enough cash to buy a home in one lump sum. And until the 1930s, there was no such thing as a bank loan specifically designed to purchase a home, something we now know as a mortgage.

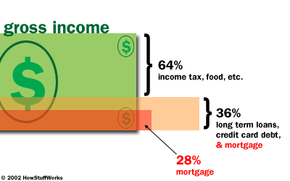

In simple terms, a mortgage is a loan in which your house functions as the collateral. The bank or mortgage lender loans you a large chunk of money (typically 80 percent of the price of the home), which you must pay back -- with interest -- over a set period of time. If you fail to pay back the loan, the lender can take your home through a legal process known as foreclosure.

Advertisement

For decades, the only type of mortgage available was a fixed-interest loan repaid over 30 years. It offers the stability of regular -- and relatively low -- monthly payments. In the 1980s came adjustable rate mortgages (ARMs), loans with an even lower initial interest rate that adjusts or “resets” every year for the life of the mortgage. At the peak of the recent housing boom, when lenders were trying to squeeze even unqualified borrowers into a mortgage, they began offering “creative” ARMs with shorter reset periods, tantalizingly low “teaser” rates and no limits on rate increases.

When you couple bad loans with a bad economy, you get rampant foreclosures. Since 2007, more than 250,000 Americans have entered foreclosure proceedings every month [source: Levy]. Now those foreclosures are turning into full-on repossessions, which are expected to reach 1 million homes in 2010 [source: Veiga].

Looking back at the flood of foreclosures since the housing crash, it’s clear that many borrowers didn't fully understand the terms of the mortgages they signed. According to one study, 35 percent of ARM borrowers did not know if there was a cap on how much their interest rate could rise [source: Pence]. This is why it’s essential to understand the terms of your mortgage, particularly the pitfalls of “nontraditional” loans.

In this article, we'll look at each of the many different types of mortgages, explain all of those confusing terms like escrow and amortization, and break down the hidden costs, taxes and fees that can add up each month. We’ll start with the most basic question: What is a mortgage?

Advertisement