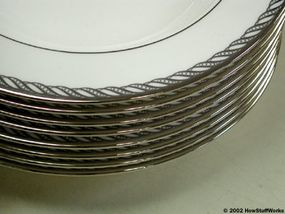

When selecting tableware for your house, you have a number of choices: earthenware, stoneware, and porcelain. You may be wondering what's the better option: bone china vs porcelain. But bone china products are actually a sub-type of porcelain. Among porcelain products, you've got basic porcelain, fine porcelain china and bone china. Many well appointed homes stock at least one, if not a combination of two or more of these options. In fact, one of the oldest standing customs for a bride and groom is registering for a china pattern.

No matter how elaborate or lovely the place setting, when it comes down to it, you're usually more concerned about what's being served on the china, rather than the china itself. But if you ever stopped to consider how china is made, you'd be amazed — it's actually fascinating.

Advertisement

In this article, we'll go behind the scenes at the Lenox factory in Kinston, NC, to see how their fine bone china is made.

China Basics

People have been making and using porcelain products for a very long time. Around the end of the 18th century, an Englishman named Josiah Spode developed a new formula for china that incorporated the use of calcined bone ash to create high quality bone china.

The addition of bone ash in china mixtures continues today at Spode as well as many other china manufacturers, including Lenox. Lenox is the only manufacturer of bone china in the United States. Considered by most to be the finest of porcelain products, bone china is stronger and has a more delicate appearance and translucent quality than the basic porcelain and "fine" varieties.

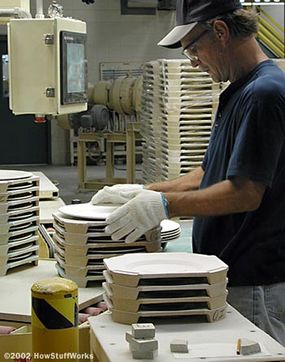

Creating bone china entails an involved series of steps carried out by a number of highly skilled individuals and some really impressive machinery. When you first enter the Lenox factory, you're immediately struck by the size of the facility (about 150,000 square feet, 14,000 square meters) — it takes a lot of space to accommodate all the equipment and the 350-member staff. Although this factory only produces bone china, what we'll find here is generally useful information because other porcelain products are made in pretty much the same way.

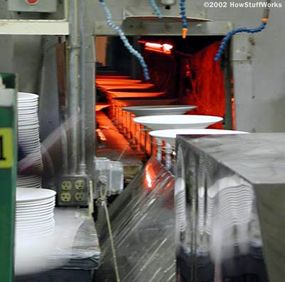

There are four main processes involved in creating china:

- Clay making

- Mold making

- Glazing

- Decorating

Another thing that stands out as you tour the Lenox facility is that all of these processes rely on the four elements. As you'll see in the next several sections, earth (the raw materials), wind (there are air hoses everywhere), fire (the kilns), and water (used during every process) are all required to make china.

Now let's take a look at how the clay is made.

Advertisement