Benjamin Franklin once said, "In this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes." A host of tax evaders have tried to get out of the latter certainty, only to end up in prison. But refusing to die -- that just seems ludicrous, right? Not to Arakawa and Madeline Gins, a husband-and-wife team known for their architecture, art and poetry. When you go to their Web site, you are greeted by the following phrase: "We have decided not to die."

Advertisement

Well, good for them, you may think as you look at the bold words. The rest of us here in the real world will keep on following the ordained pattern. But what if we didn't have to? Since Arakawa and Gins met in 1963, they have been exploring art as a way to "reverse the downhill course of human life" [source: Bernstein]. They call this pursuit "reversible destiny," which means that death does not have to be inevitable for humans.

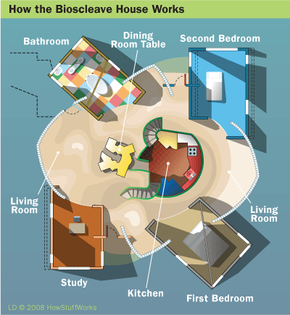

Arakawa and Gins believe we can reinvent ourselves as immortal beings by changing and challenging our perceptions. The best way to shake up our beliefs, as presented by Arakawa and Gins, is to change the very nature of how and where we live. That's why these two have designed residences that force the occupant to interact with his or her surroundings in a different way. That's the idea behind the Bioscleave House, a home constructed in New York that will have its residents living forever, if the architects are to be believed. No elixir of youth, no cryogenic freezing -- just pay the mortgage and you will not die.

Interested? Well, beyond the price of the house, there's a high price to pay for this kind of immortality: The house is not comfortable, and no real estate agent will try to convince you otherwise. All your previous expectations of a home, such as a flat floor or the occasional door, all go out the oddly placed window at the Bioscleave House. And that's exactly the point. Arakawa and Gins don't want you to be comfortable, because comfortable complacency could lead to death. You'll need to stay on your toes to stay alive.

So can this house really prevent death? What architectural features will keep us alive? We'll peek inside the Bioscleave House on the next page.

Advertisement