Key Takeaways

- Studies have shown that bug zappers may not be effective against mosquitoes and biting gnats, as they often attract and kill non-target insects, which can disrupt local ecosystems.

- Alternatives to traditional bug zappers include devices that emit carbon dioxide, Octenol and moisture to attract mosquitoes, with some claiming to collapse entire mosquito populations by targeting egg-laying females.

- Personal protection strategies against mosquitoes include eliminating standing water, using insect repellents containing DEET and utilizing citronella products, although no perfect mosquito-control device exists yet.

While you have fun outdoors, many insects get to enjoy a good meal. Either they're eating your food or they're eating you. To clear your yard of these insects, you can try a variety of devices, ranging from simple Citronella candles to elaborate traps to pesticides (such as Dursban) to electronic bug zappers. A bug zapper, more formally known as an electronic insect-control system or electrical-discharge insect-control system, lures bugs into it and kills them with electricity. In this article, we will examine the parts of a bug zapper, learn how this device works and discuss the controversies surrounding its use. We'll also look at some other bug-control devices that may make your time outdoors more pleasant.

Inside a Bug Zapper

The first bug zapper was patented in 1934 by William F. Folmer and Harrison L. Chapin (U.S. patent 1,962,439). Although there have been many improvements, mostly in the areas of safety and lures, the basic design of the bug zapper has remained the same.

Advertisement

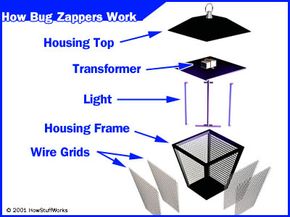

Bug zappers are incredibly simple. The basic parts of the bug zapper are:

- Housing - Exterior casing that holds the parts The housing is usually made of plastic or electrically grounded metal and may be shaped liked a lantern, a cylinder or a big rectangular cube. The housing also may have a grid design to prevent children and animals from touching the electrified grids inside the device.

- Light bulb(s) - Fluorescent light that attracts insects, usually mercury, neon or ultraviolet (black light)

- Wire grids or screens - Wire meshes (usually two) that surround the light bulb and are electrified to kill insects

- Transformer - Device that electrifies the wire mesh, changing the 120-volt (V) electrical-line voltage to 2,000 V or more

The increased voltage supplied by the transformer, at least 2,000 V, is applied across the two wire-mesh grids. These grids are separated by a tiny gap, about the size of a typical insect (a couple of millimeters). The light inside the wire-mesh network lures the insects to the device (many insects see ultraviolet light better than visible light, and are more attracted to it, because the flower patterns that attract insects are revealed in ultraviolet light).

As the bug flies toward the light, it penetrates the space between the wire-mesh grids and completes the electric circuit. High-voltage electric current flows through the insect and vaporizes it. You often hear a loud "ZZZZ" sound when this happens. Bug zappers can lure and kill more than 10,000 insects in a single evening. By design, bug zappers do not discriminate between types of insects, but because of their luring strategy, they tend kill those insects that are most attracted to ultraviolet light. Mosquitoes, unfortunately, are not attracted to ultraviolet light.

We'll look at bug zapper controversies and other bug zapping methods in the next section.

Advertisement