Are you a friend on the outs who wants to skip the drama of a face-to-face "My bad"? Then place a lemon verbena plant on your bestie's front stoop and feel the scales of justice begin to balance with forgiveness. Or maybe you're a vocabulary challenged suitor with a conspicuous heart tattoo who feels "some kind of way"? Present your special someone with a heliotrope bouquet (for infatuation) and hear your inner angels sing. You don't have to be a flower whisperer or a garish yellow emoticon to express what's going on deep down inside. With a little research and a hint of purposeful resolve, practically any emotion, or lack thereof, from apathy (candytuft) to zeal (elderflower), can be conveyed with a just-right flower.

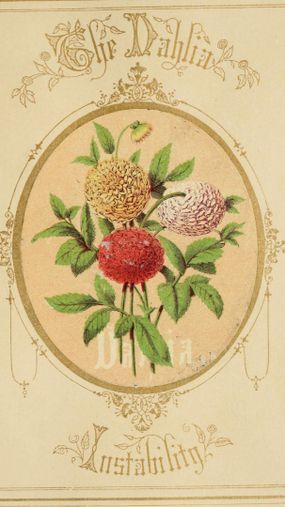

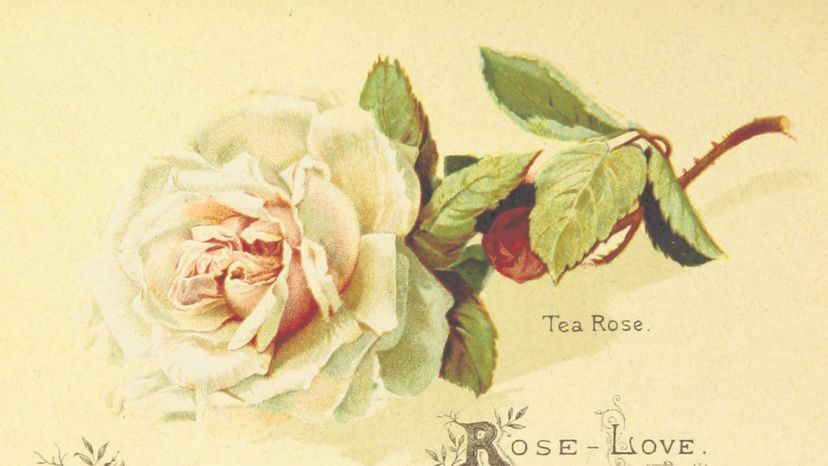

Floriography — the association of flowers with special virtues and sentiments — has been a practice from antiquity to the present day. Ancient Chinese flower calendars established the tradition of associating seasonal flowers with meanings beginning in the seventh century B.C.E., making January's winter flower, the plum blossom, a symbol of beauty and longevity. By the 1700s, the concept of selam, the Turkish language of flowers and objects, found its way to Europe, further establishing the idea of associating flowers with meanings.

Advertisement

"For there is a language of flowers. For there is a sound reasoning upon all flowers. For elegant phrases are nothing but flowers," eulogized the religious visionary and madman poet, Christopher Smart (aka "Kit," "Kitty," "Jack" and "Mrs. Mary Midnight") in lines from his now-revered masterpiece, "Jubilate Agno," which he penned in mid-18th century London during yearslong confinement at St. Luke's Hospital for Lunatics and at Mr. Potter's private madhouse.

(One cannot help but wonder what Mr. Smart might conclude — So I'm the one locked up in a madhouse? — were he able to gaze through his 18th-century lens upon the poetic playground of today's social media at the prevalence of certain plant-based emoji: Look away, Mrs. Midnight! Eggplant, peach, tulip — have you no shame?)

Advertisement