Greenhouses are often seen as romantic structures. Originally the exclusive property of the wealthy and wellborn, the first greenhouses were probably built in Roman times to cultivate exotic fruits and vegetables. In the first century, Pliny the Elder made a reference to the Emperor Tiberius having had a portable greenhouse that was protected with a covering made of transparent stone [source: Janick]. This unusual and rare greenhouse was devised to cultivate the emperor's favorite vegetable, the cucumber.

Produce that we can find today in most local grocery stores was at one time considered priceless in many parts of the world. In the 17th century, entire buildings were erected to house and propagate oranges and pineapples. Before they were called greenhouses, the names for these structures were as exotic as the fruits they contained. They were called specularia, orangeries and pineries.

Advertisement

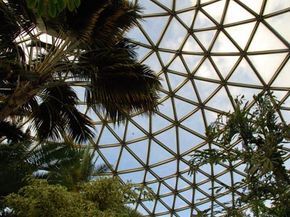

Reproducing plants out of season gave man a measure of control over nature. The allure of it sparked the imagination and inspired new methods for building structures devoted to plants. Precious glass began to be used more and more in greenhouse construction. Harnessing the plant world and exploring the possibilities of cultivating useful, exotic species led to building larger and more elaborate greenhouses, some of which are still in existence today.

This fascination with propagating plants in a controlled and protected environment has never dimmed. Greenhouses have grown from a novelty to an essential component in the way we feed hungry populations around the world, cultivate plants for medical research and preserve plants for future generations to enjoy. In this article, we'll see how greenhouses work to make all of this happen and why you may just want a greenhouse in your backyard.