If you're like most people, you've probably never thought long and hard about concrete. Sure, its gray presence is all around us -- in our roads, bridges, parking lots and driveways -- but there can't be that much to it, right? A truck pulls up, dumps it in a defined area, and it hardens. Voila. A sidewalk is born. But you might be surprised how many ways boring-old-concrete can be mixed and cast, even for use in your own home. In fact, one "recipe" has become so popular in the last half century that you'll find it in everything from kitchen countertops to China's Three Gorges Dam, the largest hydroelectric project in the world. What is this incredibly versatile, uber-strong building material? The answer is fluid concrete.

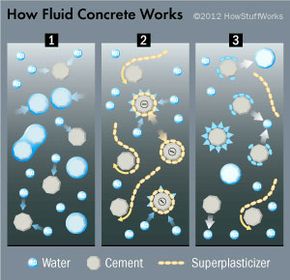

All concrete starts out as a mixture of water, cement and some type of aggregate (like sand and gravel) and hardens thanks to a chemical reaction that occurs between the water and the cement (which we'll discuss on the next page). Ideally, concrete should have just enough water in it to react completely with the cement -- any more or less water will weaken the end product. The result is concrete with a low slump, which is an engineer's fancy way of saying that it has a very thick consistency when wet. While concrete with a low slump makes for strong hardened concrete, it's difficult to work with when it's wet because it's not thin enough to ooze into tight spaces. Fortunately there are admixtures, or chemical additives, that can thin the concrete without weakening it (the way adding more water to the mixture would). One such admixture, called a superplasticizer, is used to make fluid concrete. The superplasticizer's superpower is that it lends concrete a high slump without stealing its strength. Concrete with superplasticizers in it is very fluid when wet and very strong when hardened.

Advertisement

While natural concrete has been around for 7,000 years and modern portland cement concrete has been used for about 200 years, fluid concrete is a much newer invention. Ancient experimenters tried thinning concrete with organic materials like milk, blood (yes, blood), and lard with little success. It wasn't until the late 1950s and early 1960s that engineers in Germany and Japan first developed superplasticizers. The substance hit the market in 1964 and was first made available in the United States in the mid-1970s. By 1984 an estimated 90 to 100 million cubic yards (1.5 to 2.3 million cubic meters) of fluid concrete had been produced [source: Mielenz]. Today its use is widespread. Contractors love the fact that it pumps easily, fills in narrow spaces, and requires little or no compaction to remove air bubbles, all while retaining its high strength.

But of course they have science to thank for these miracle benefits. How do superplasticizers do their job?

Advertisement