Beyond the written word, building with stone is one of the oldest and most enduring arts of human culture. There are stone walls in Britain -- still standing -- that date back to 3500 B.C. These days, there are much simpler, cheaper and faster ways to define our outdoor spaces, but none of them carry the precise character or look of a stone wall. That's the reason we still value them, whether living in the middle of a city or out on a farm. The simplest ingredients -- stone, gravity, ingenuity -- still create, for some of us, the most perfect solution.

Make no mistake. You're involving yourself in quite a project if you choose to build this way. Stone is neither light to carry nor easy on your wallet, and when building a wall, the brainpower involved can be just as important as the brawn you'll be using. Just think of the stone walls that have been part of the New England landscape for decades, or the miles of wall standing in the United Kingdom for hundreds of years ... and how yours could still be standing centuries from now.

Advertisement

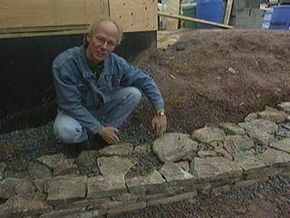

In this article, we'll talk about the options available -- and decisions to be made -- for building your wall, as well as the tools and materials you'll need. We'll focus primarily on the dry-stone technique, although these days almost any stone building project involves at least a little concrete. Mortared walls, which are constructed by applying a construction paste in between the stones as a fixative, are the other major option here and are very popular, but we'll concentrate mostly on the former: Dry-stone walls rely almost entirely on gravity to keep their enduring shape, and thus take more work to build correctly. However, many of the details apply to either project.