Most people carry five to 10 keys with them whenever they go out. On your key ring you might have several keys for the house, one or two more for the car and a few for the office or a friend's house. Your key ring is a clear demonstration of just how ubiquitous lock technology is: You probably interact with locks dozens of times every week.

The main reason we use locks everywhere is that they provide us with a sense of security. But in movies and on television, spies, detectives and burglars can open a lock very easily, sometimes using only a couple of paper clips. This is a sobering thought, to say the least: Is it really possible for someone to open a lock so easily?

Advertisement

In this article, we'll look at the very real practice of lock picking, exploring the fascinating technology of locks and keys in the process.

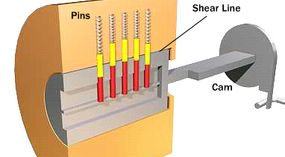

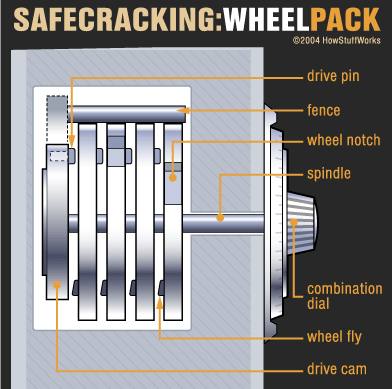

Locksmiths define lock-picking as the manipulation of a lock's components to open a lock without a key. To understand lock-picking, then, you first have to know how locks and keys work.

Locks come in all shapes and sizes, with many innovative design variations. You can get a clear idea of the process of lock picking by examining one simple, representative lock. Most locks are based on fairly similar concepts.

For most of us, the most familiar lock is the standard dead-bolt lock you might find on a front door. In a normal deadbolt lock, a movable bolt or latch is embedded in the door so it can be extended out the side. This bolt is lined up with a notch in the frame. When you turn the lock, the bolt extends into the notch in the frame, so the door can't move. When you retract the bolt, the door moves freely.

A deadbolt lock's only job is to make it simple for someone with a key to move the bolt but difficult for someone without a key to move it. In the next section, we'll see how this works in a basic cylinder lock.