You don't often see a home for sale advertised as "dirt cheap." You certainly won't find many contractors who brag about a dirt cheap building method. A dirt cheap price for a home might just signify a money pit, a disaster in the making. An exception to that rule, however, might be building with actual dirt.

Advertisement

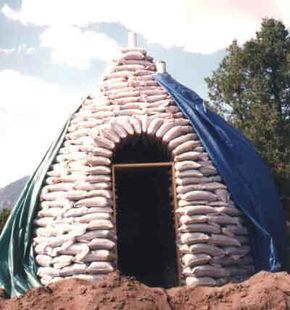

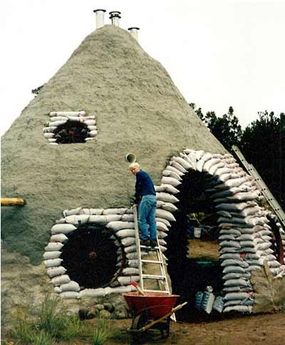

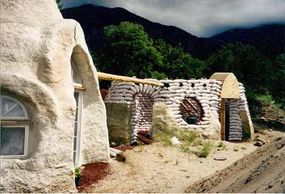

Earthbag homes are exactly what they sound like -- bags filled with earthen materials stacked to make a house. They often look like big beehives when they're completed, but it's possible for them to take other forms as well. Sandbags have long been used to create military bunkers and flood walls, but their role in building homes is fairly new.

In the 1970s, Iranian architect Nader Khalili was working in the countrysides of Iran, teaching villagers how to make their adobe homes solid by a process that was like firing clay in a kiln. When he came to the United States, however, he realized that adobe homes weren't always practical or economical but that elements of the earth could still be used to create a stable home that anyone could afford.

Khalili, who established the California Institute of Earth Art and Architecture in Hesperia, Calif., identified sand as a resource that was available to everyone. He began stacking sandbags like bricks, using barbed wire as a kind of mortar. Eventually, Khalili developed superadobe, which is a building method that uses mile-long fabric tubes that can be pumped full of soil and laid in coils to create a structure. Khalili saw these superadobe earthen structures as a way to provide temporary housing in the case of natural emergencies, low-cost housing for the poor and even lunar housing, with astronauts taking the tubes to the moon and using materials there as fill. He presented this idea to NASA and built a prototype lunar colony in Hesperia.

You don't have to go all the way to the moon or California to find an earthbag structure. Earthbag homes are a way to build a house with natural materials that are literally right in your own backyard. But are they safe? How do you build one? And why would you want to? We'll look at the benefits of earthbag construction on the next page.

Advertisement