What do Oregon campers and ancient Mongolians have in common? A love of yurts.

A yurt is a circular lattice-walled tent. They've been used throughout history by nomads in Central Asia. Evidence of fourth century B.C. yurts has been discovered, and the oldest complete yurt was found in a 13th century Mongolian grave [source: King]. The structures were well-suited for the nomadic lifestyle because only a few oxen were required to carry a family's entire home. But the structure was also easy to heat in the cold Mongolian winters where temperatures might reach 50 degrees below Celsius (-58 degrees Fahrenheit) [source: King].

Advertisement

Oregon is nowhere near as cold, but campers still appreciate a yurt during that temporary nomadic period known as a vacation. When state parks in Oregon were faced with a budget crisis, in part due to a lack of people camping in the off-season, a parks manager decided to install yurts. Campsites around the country copied him mostly because the structures take less work and provide more comfort than a tent, particularly for young families or older people. Beyond camping, though, many people are using yurts for permanent homes, offices and schools.

While other countries have discovered the appeal of yurts only recently, many Mongolians continue to live in the structures their ancestors developed, which they know by the word ger, which means home. The term "yurt" is derived from the Russian term for the dwelling, and just as the Russians gave this structure a new name, other cultures have adapted the Mongolians' home for their own needs.

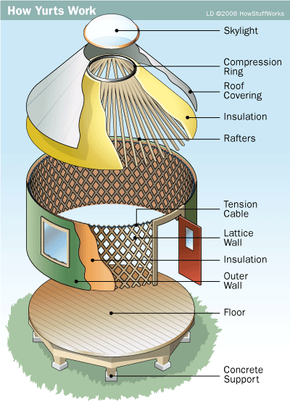

In this article, we'll look at the yurt's humble beginnings in Mongolia and the luxury yurts that exist today, as well as the reasons why the makeshift homes appeal to so many people. On the next page, we'll investigate the structural elements that keep a yurt standing against the strongest winds yet allow a person to take it down in less than an hour.

Advertisement