Assessing Unfinished Furniture

Out of all the different types and styles of unfinished furniture, how do you know which pieces are worth buying? And once you locate a good piece of unfinished furniture, how do you distress it and give it that antique feel?

These are the questions we'll answer in the next few pages. We'll start at square one, by telling you what to look for when selecting unfinished furniture.

Advertisement

Assessing Unfinished Furniture

Price, unfortunately, is the first indicator. You really get what you pay for with this furniture. Before you buy any unfinished piece, comparison shop to get an idea of what's available. Most unfinished furniture is pine, but some is made with other woods. Whatever type of wood is used, the quality of the wood and the workmanship that goes into the piece can vary tremendously.

When you find a piece of furniture you like, take a good look at it. Is the wood clear or full of knots, smooth or rough? Cheap furniture is usually knotty and sap-streaked; the more expensive pieces are made with better-quality wood. What state is the wood in? Cheap furniture is probably raw, and may have rough edges and deep saw gouges. Good unfinished furniture is often already sanded, ready for finishing.

Another important consideration is how well the piece of furniture is made. Most unfinished furniture is assembled with staples driven by a power staple gun. Unless the stapling is carefully done, the joints may not be secure. How sturdy is the piece? Does it have wobbly legs, or are parts of it poorly fastened together? You can fix loose joints, but it's hard to salvage a piece that's badly matched or falling apart completely.

Are doors and drawers aligned properly, and do they work smoothly? If they don't, is it because they're the wrong size for the opening or because of loosely or inaccurately fastened hardware or drawer guides? You can deal with mechanical problems, but a part that's too big or too small can never be adjusted. Examine all moving parts to make sure they're cut, joined, and assembled properly. Finishing can do a lot, but it can't remake a shoddy piece.

The style of the funiture also is important. Look at the style. Do you like the lines of the piece? Will it do the job you want it for? Don't settle for a piece of furniture that's the wrong size or style; it isn't worth working on something you don't really want. On the other hand, a piece of furniture that's basically right can be given any character you like with different hardware, trim moldings, decorations, or special finishes.

Before you make a final decision, assess the work you'll have to do to get the piece ready to finish -- cleaning out knotholes and sap pockets, regluing legs, renailing drawers, repairing splits, smoothing splintered edges, changing hardware. How much time and effort will it take? How much hardware and trim will you have to add? Are the size and style right? Do you like the wood? How much are you saving by buying the piece unfinished? It all comes down to one basic question: Is it worth it? If you choose carefully, it is.

Assessing Surface Damage

No matter how carefully you shop, unfinished furniture is likely to have a few problems. The joints may be loose; moving parts may stick. There are usually a few knots in the wood, and these will bleed through the finish if they aren't sealed. There are almost always rough edges or saw marks. Before you distress the wood, take the time to deal with these problems. Your results will more than justify the effort.

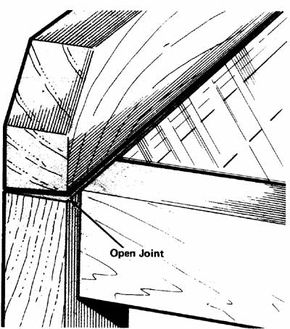

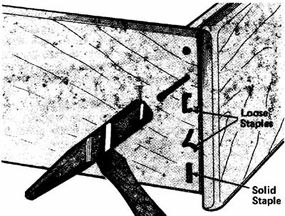

Loose joinery and poor assembly: The first step in working with unfinished furniture is making sure it's solid. Examine the joints to locate any weak points; drawers are especially likely to need refastening. If the staples or other fasteners are solid, renailing may not be needed, but if they're off-center or don't look very secure, reinforce them by driving finishing nails next to them. Drill pilot holes for the nails to keep the wood from splintering. If the staples are loose, pull them out with pliers, and renail the joint. Fill the staple holes with wood filler.

Loose legs, rungs, arms, or spindles should be reglued. Test all parts of the piece to make sure they're secure, and reglue or refasten any loose part.

If the piece has drawers, they should work smoothly. Check the drawer guides, inside the frame, and the runners on the bottom edges of the drawer. They should be square and securely fastened, with no protruding nail heads. Refasten the guides or runners, if necessary, and countersink protruding nail heads with a nail set.

Knots and sap pockets: Examine the wood carefully for spots where sap has flowed or resin beaded on the surface. Scrape off hardened resin, and clean knots and sap pockets with turpentine on a soft cloth. If large knots are loose, remove them entirely; then apply carpenters' glue around the edges and replace the knots, flush with the surface.

If small knots are loose -- pin knots -- remove them completely and fill the holes with wood plastic or water putty. Seal all knots and sap pockets with a coat of 1-pound-cut white shellac; if the shellac is completely absorbed, apply two or more coats, as needed, to seal the knots completely.

Rough edges: To correct surface roughness, sand the edge smooth. If there are low spots or gaps in an edge, fill them with wood filler or water putty and then sand the filler smooth. Square edges should be very slightly rounded before finishing; smooth and round them with fine-grit sandpaper on a sanding block. Do not plane edges; planing could splinter the wood.

Saw notches and splinters: Dull saw blades leave notches and splinters, and you're likely to find these problems anywhere the wood has been cut or joined. If the notches are very shallow, you may be able to sand them out. In most cases, you'll have to fill them with wood plastic, and then sand the filler smooth.

Now you're ready to begin the process of distressing the wood, which is covered on the next page.