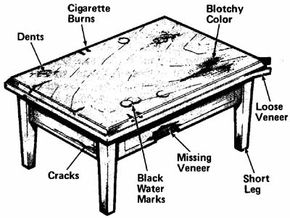

Is Grandma's hand-me-down china hutch looking a little worse for wear? How about that coffee table the kids just can't seem to remember not to put their sippy-cups on? Instead of just tossing out those favorite furniture pieces that are showing their age, why not take on a refinishing project?

In this article, you'll find dozens of tips that will walk you through the process of refinishing wood furniture -- the right way. You'll find:

Advertisement

- Staining Wood Furniture Basics Get a quick overview of what actually goes into staining wood furniture on this page. Learn why it's important to strip off the old finish thoroughly and what other preparation measures you may have to take to ensure the wood is ready to take a stain.

- How to Remove Furniture Stains and Discoloration One of the most important steps in furniture refinishing is getting rid of stains and discoloration from the wood. If you take care of this before you apply a new stain, you'll be amazed at how great the refinished piece looks. Learn some tips for removing stains on this page.

- How to Bleach Wood Furniture Sometimes discoloration in wood needs a little more elbow grease and a little bit stronger solution. That's where bleaching techniques come in. Be sure to read this section before attempting to bleach wood, however. Some woods don't take to bleaching well, so you don't want to ruin your piece by not being informed.

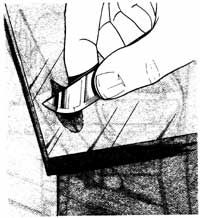

- How to Repair Furniture Scratches, Dings, and Dents Most dings and dents in wood furniture can be easily repaired with the helpful techniques outlined in this section. If the scratch is significantly deep, however, you'll need to do a bit more work. Find out how to assess and repair all types of dings here.

- How to Repair Furniture Cracks and Gouges Some damage to wood furniture is a bit more serious than a scratch or a dent. If you're faced with cracks and gouges, don't dispair. The helpful techniques on this page will set you in the right direction.

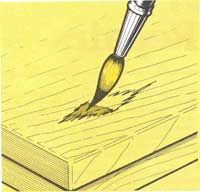

- How to Repair Furniture Burns Don't get all fired up about a burn on your wood furniture. Just like other damage, a scorch mark can be repaired with some simple techniques. You'll learn how to repair all kinds of burns, including the most common -- cigarette burns -- on this page.

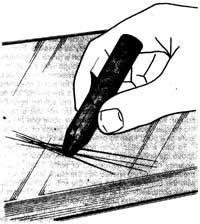

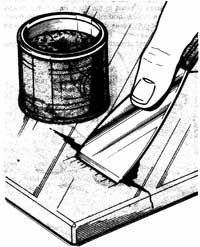

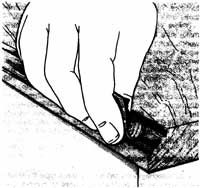

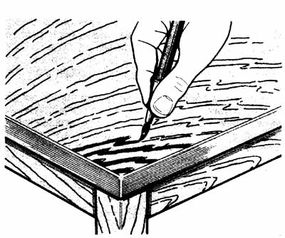

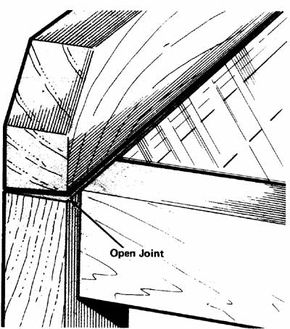

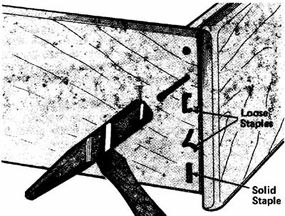

- How to Repair Furniture Veneer Veneer is a thin layer of wood attached with glue to a solid base. And because it is so thin, it is prone to damage. Learn how to repair a veneer surface in this section, including fixing blisters, chips, cracks, and more.

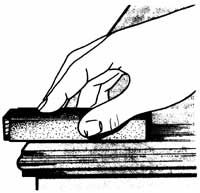

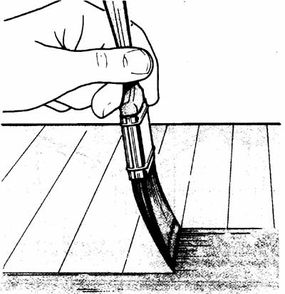

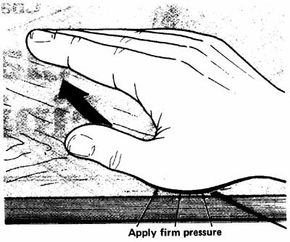

- How to Sand Wood Furniture Another crucial step in refinishing furniture is sanding. The better you prep your surface for staining, the better the wood will take the stain. This page offers tips on sanding technique as well as suggestions on what type of sandpaper and steel wool to use on the job.

- How to Choose a Furniture Stain Choosing a stain not only depends on the look you're trying to achieve but also on what type of wood you're working with. Learn more about choosing a stain in this section, including descriptions of the various stains available today.

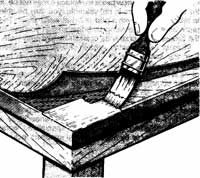

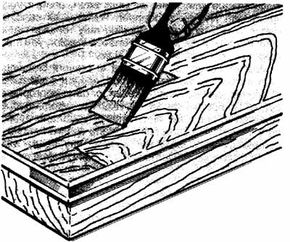

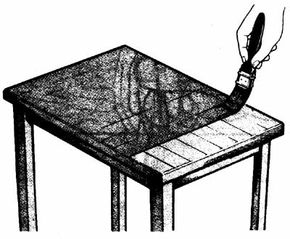

- Staining Techniques for Wood Furniture Brush up on staining techniques for wood furniture on this page. You'll learn how to apply the various types of stain to get the best coverage, and what you need to do to after you've applied the stain. Also find out what types of wood work well with lightening stains.

- How to Choose a Furniture Finish After all the hard work you've put into repairing, sanding, and staining your piece, you want to make sure it looks good for years to come. That's where furniture finishes come in. Take a look at this page for tips on how to choose a furniture finish.

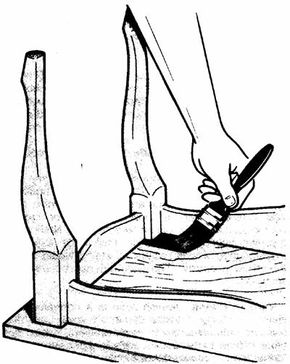

- How to Varnish Furniture Varnish is probably the most popular wood furniture finish because it not only enhances the look of the wood but is very durable. On this page, you'll learn about the types of varnishes available and how best to apply them to your wood piece.

- How to Apply a Penetrating Resin Furniture Finish Like varnish, penetrating resin is very durable to wear and tear. However, this type of finish actually soaks into the wood, so it is not ideal for all wood types. Learn more about penetrating resin and how to apply it in this section.

- How to Shellac Furniture Shellac is very easy to apply, but unfortunately, this furniture finish is not very durable. That doesn't mean it isn't worth using, however. Since shellac creates such a beautiful finish, it is often used on find wood pieces that don't withstand a lot of wear and tear. Find out more about shellac on this page.

- How to Lacquer Furniture In general, lacquer is very difficult to work with and must be applied in several very thin coats in order to get the desired finish. If you just must use lacquer on your wood piece, take a look at the tips on this page before you begin.

- How to Wax and Seal Furniture While not the most long-lasting solution, wax and sealer stain finishes are relatively easy to apply and can add some necessary color to blotchy wood. Find out when it's best to use waxes and seals on your furniture in this section.

- How to Apply Oil Finish on Furniture The purpose of oil finishes is to bring out the natural beauty of the wood. Because of this, oil is only useful with certain woods and with certain types of furniture. Learn about some of the most popular oils -- Danish and tung oil finishes -- on this page.

- Assessing Unfinished Furniture There are several things you should look out for when purchasing unfinished furniture, including the type of wood used, if the joints are secure, and if the piece is well sanded and ready for finishing. Find these tips and more in this section.

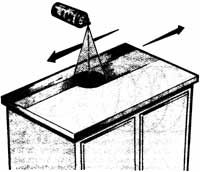

- Distressing Unfinished Furniture When working on a piece of unfinished furniture, you often want to give the piece a little bit of character so it doesn't look so brand new. Learn distressing techniques on this page, including how to make sure to don't distress too much and end up with a battered look.

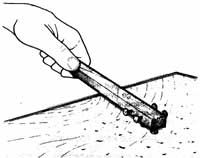

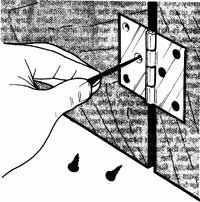

- How to Repair Furniture Hardware After all your efforts at refinishing, it would be a shame if your piece lost its luster because of shoddy furniture hardware. Learn how to repair furniture hardware on this page to make sure your piece not only looks good but functions well.