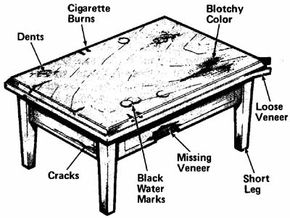

In most cases, bleaching is essentially a first-aid measure, not a routine part of refinishing. A piece of furniture should be bleached if the surface is marked by stains, black rings, or water spots; if the wood is discolored or blotchy; if the color is uneven; or if an old stain or filler is left after the finish is removed. Old filler is often a problem with oak, walnut, and mahogany. Bleaching can also be used to even the color of a piece of furniture made with two or more woods. It can lighten the darker wood to match the lighter one.

Before you use bleach on any piece of furniture, make sure the wood is suitable for bleaching. Some woods don't accept bleach well -- cherry and satinwood, for instance, should never be bleached. Some woods, such as bass, cedar, chestnut, elm, redwood, and rosewood, are very difficult to bleach, and some -- notably pine and poplar -- are so light that bleaching makes them look lifeless. Birch, maple, and walnut can be bleached, but bleaching destroys their distinctive color. And the rare woods -- mahogany, teak, and the other choice woods -- seldom benefit from bleaching. Common woods that are easy to bleach, and may benefit from it, include ash, beech, gum, and oak.

Choosing a Bleach

Not all bleaching jobs call for the same type of bleach. Depending on the problem you want to correct, you may need a very strong bleaching agent or a relatively mild one. Below are some common bleach options you might want to consider.

Laundry Bleach: This mild bleach can solve most refinishing color problems, from stain or filler not removed in stripping to ink stains and water spots. It works well for blotchy areas and for slight overall lightening, but it won't change the color of the wood drastically. Before you use a stronger bleach on any piece of furniture, try laundry bleach; it usually does the trick.

Oxalic Acid: Oxalic acid, sold in powder or crystal form, is used to remove black water marks from wood. It is also effective in restoring chemically darkened wood to its natural color. You're not likely to encounter this problem unless you have a piece of furniture commercially stripped because lye and ammonia, the chemicals that discolor wood, are not recommended for nonprofessional use. Oxalic acid must be used on the entire surface of the wood, because in most cases it also bleaches out old stain. You may have to bleach the entire piece of furniture to get an even color. Oxalic acid is more effective in lightening open-grained wood than close-grained.

Two-Part Bleaches: The two-part commercial wood bleaches are used to lighten or remove the natural color of wood. If you want a dark old piece to fit in with a roomful of blond furniture, this is the bleach to use. Two-part bleach is very strong and must be used carefully; wear rubber gloves and safety goggles. This type of bleach is also expensive. Several brands are available.

Bleaching Techniques

Whatever bleach you use, remember that the results are permanent -- you may be able to restain if you make the wood too light, but uneven bleaching is very hard to remedy. Make sure the wood is absolutely clean, and touch it as little as possible. The bleach must penetrate the wood evenly.

Before applying the bleach, test it on a scrap piece of the same wood or on a hidden part of the piece of furniture. Make sure you know exactly what the bleach will do and how fast. In general, bleaches act quickly on soft woods and slowly on hard woods.

Bleaching isn't difficult, but it does require some precautions -- bleaches are fairly strong chemicals. The stronger ones can damage skin, eyes, and lungs. Wear rubber gloves and safety goggles when working with bleach, and make sure your working area is well ventilated. Follow the bleach manufacturer's instructions exactly. If you get bleach on your skin, wash it off immediately.

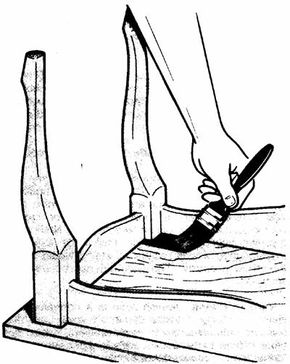

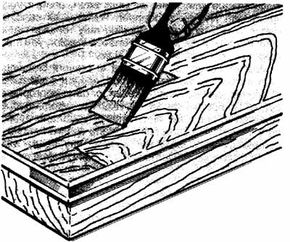

Bleaching also requires careful application and removal. With any bleach, use a synthetic-bristle brush -- the chemicals will damage natural bristles. Apply the bleach along the grain of the wood, wetting the surface evenly and thoroughly; there should be no dry spots and no puddles. Let the bleach work as detailed below.

After bleaching, wipe the wood clean with a damp cloth. To remove any residue, neutralize the wood thoroughly; use an ammonia solution for oxalic acid, a borax solution for laundry bleach or two-part bleaches. Wash the bleached wood thoroughly with the appropriate neutralizer; be careful not to overwet it. Then, working quickly to prevent water damage, rinse the wood with clean water and dry it thoroughly with a soft cloth. Let the piece of furniture dry for at least two days before doing any further work on it.

Laundry Bleach

Apply laundry bleach full-strength, brushing it evenly over the entire surface. If you're removing spots or lightening discolored areas, apply bleach full-strength to those areas. Laundry bleach works quickly. After a minute or two, you should be able to see the stain fading. If you're bleaching out an old stain, wipe the bleach off with a damp cloth when the stain has lightened.

If you're spot-bleaching to remove spots or blend color areas, wait until the bleached spots are roughly the same color as the rest of the wood; then apply bleach again over the entire surface. Remove the bleach with a damp cloth when the color is even. Finally, neutralize the treated wood with a solution of 1 cup of borax dissolved in 1 quart of hot water. Neutralize, rinse with clean water, and dry it thoroughly.

Oxalic Acid

Oxalic acid is not caustic, but it is poisonous. Wear rubber gloves and safety goggles, and make sure ventilation is adequate. To prepare the acid, mix a saturated solution with warm water: 1 ounce of powder or crystals per 1 cup of warm water. Make sure you prepare enough bleach to treat the entire surface or piece of furniture.

Apply the acid solution evenly to the wood, brushing it on along the grain to cover the entire surface. On soft wood, you'll see results very quickly; on hard woods the bleaching takes longer. Let the acid work for about 20 minutes, then wipe it off with a damp cloth. If the surface isn't fully or evenly bleached, reapply the acid as necessary. On hard woods, complete bleaching may take up to an hour. Wipe the wood clean with a damp cloth, and wash it with clean water. Then neutralize it with a solution of 1 cup of household ammonia and 2 quarts of water. Rinse it again with clean water, and dry it thoroughly.

Two-Part Bleaches

Two-part bleach is easy to use, and usually works very quickly. The two components of the bleach -- labeled "1" and "2" or "A" and "B" -- are usually applied separately. Read the manufacturer's instructions and follow them exactly. The first solution is usually allowed to work for about 20 minutes before the second solution is applied.

Following the directions carefully, apply the first solution and let it work; then apply the second solution. One treatment usually bleaches the wood completely, but if the wood isn't light enough, treat it again. Wipe the bleached wood clean with a damp cloth, and then neutralize it with a solution of 1 cup of borax dissolved in 1 quart of hot water. Rinse the wood with clean water, and dry it thoroughly.

Post-Bleach Treatment

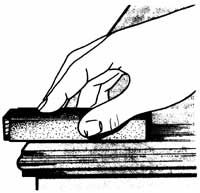

Treatment with any bleach raises the grain of the wood, even when the piece of furniture has already been thoroughly sanded. To prevent the raised grain from affecting the finish, it must be resanded to the level of the wood surface after the wood is dry.

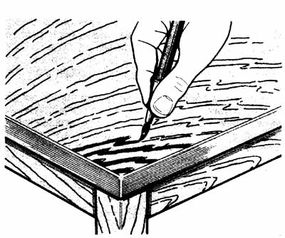

After bleaching, let the piece of furniture dry for at least two days. Then sand the grain down lightly with grade 5/0 or 6/0 sandpaper; be careful not to roughen the surface. Because there may still be some chemical residue in the wood, wear a breathing mask and use a vacuum to remove sanding dust. Wipe the wood clean with a tack cloth.

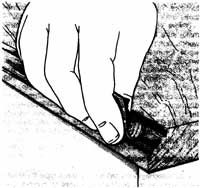

One other complication of bleaching, especially with laundry bleach, is that the wood may be left with a whitish or grayish color. This is not serious; it indicates that the bleach has dried out the fibers of the wood surface. On hard woods, it disappears when the finish is applied. On soft woods, the gray color may be pronounced and the loose fibers obvious. To remove them, rub the wood firmly along the grain with No. 000 steel wool; rub the entire bleached area, and make sure the color is even. The grayish cast will disappear completely when the finish is applied.

You're almost ready to start staining your furniture, but there's one more crucial step. Before you can apply any sort of finish to wood, you have to prepare the surface by sanding it down. In the next section, you will learn all about sanding, including how to get into those tricky, tight spaces.